Towards the end of the creative peak-era of Will Eisner's weekly comic book/strip The Spirit, the Eisner Studio had a strong team churning out innovative comics material.

Writers Jules Feiffer and Marilyn Mercer, background artist Jerry Grandenetti and peerless letterer Abe Kangeson were key components in a finely-oiled funnybook machine. All contributed greatly to the high quality of the post-war Spirit feature. (Other notables who contributed to post-war Eisner product include Klaus Nordling, Andre LeBlanc and Dan Barry.)

Eisner's hand was still deeply felt in the series. His growing ambitions to push comics past their humble street-smart status, and into something that rivaled literature and cinema, found their first strong expression in the 1946-1950 run of The Spirit.

Although Eisner certainly leaned heavily on his creative team, he left his distinct imprint on the work that issued from his studio. He drew from their strengths and made their distinct talents assets in mass media work of high quality

Although Eisner certainly leaned heavily on his creative team, he left his distinct imprint on the work that issued from his studio. He drew from their strengths and made their distinct talents assets in mass media work of high quality

A lesser-known side project of the post-war Eisner Studio appeared in the checkered pages of a comic magazine published by Fiction House. Their comix imprint was as "spicy" and lowbrow as their pulp magazines. Cleavage, violence and sexual suggestion are rife in the assembly-line Fiction House product.

Much of their comix material came from the shop of Eisner's old partner, S. M. Iger. Iger's shop had a distinct house style. By this time, the look and feel keyed off of the work of African-American cartoonist Matt Baker.

Baker, a gifted artist, brought a sheen and flair to his often-elegant work. Those who followed his lead, in the manner of assemblymen on a production line, produced anonymous, efficient, prosaic work.

Baker, a gifted artist, brought a sheen and flair to his often-elegant work. Those who followed his lead, in the manner of assemblymen on a production line, produced anonymous, efficient, prosaic work.

Recognizable comix stylists such as George Evans, Bob Lubbers and Jack Kamen did work for Fiction House. Their styles were slightly at odds with the Iger shop "house style," but conformed to the same general rules of lush rendering, competent drawing and static, highly repetitive staging.

The work of a Will Eisner was bound to stand out in such company. Exactly why Eisner sought to return to comic books isn't clear. His studio can't have made much money off such work. Perhaps Eisner did it to keep his staff busy enough to work full-time for him. I'm sure Eisner must have discussed this move somewhere in the vast body of interviews he left behind.

In a posthumous tribute issue of Comic Book Artist, sundry comix professionals and historians pay tribute to Eisner and his legacy. Among them is Jerry Grandenetti. He was chosen to do the artwork for a short-lived but feverishly ambitious comic book feature, "The Secret Files of Doctor Drew."

The series ran in issues 47 through 60 of Ranger Comics, amidst the headlight-heavy likes of "Firehair," "Jan of the Jungle" and "I Confess."

The series ran in issues 47 through 60 of Ranger Comics, amidst the headlight-heavy likes of "Firehair," "Jan of the Jungle" and "I Confess."

Grandenetti contributed the highly atmospheric, intensely detailed background drawings to Eisner's late-1940s Spirit. As Eisner's interest in the series lessened, throughout 1951, Grandenetti was among the artists who took over the artwork on the feature. At the time of "Dr. Drew"'s birth, Eisner was still heavily invested in The Spirit. Some of the finest episodes of the series appeared in 1949 and 1950.

Eisner created the "Dr. Drew" concept--of a self-appointed investigator of supernatural occurences, a sort of mystical-yet-worldly detective that one could imagine portrayed by George Sanders or Herbert Marshall. It's a sound idea, as it bridges Bram Stoker-style occult atmospherics with the 20th century private-eye genre.

The feature anticipates Steve Ditko's Doctor Strange, and, to an extent, the beloved 1970s TV series Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Its mixture of Old World atmosphere and modern themes is genuinely unusual, and compelling.

In 1949, Eisner and Co. clearly chafed at the generic restrictions of the weekly Spirit feature. Increasingly, the series' focus shifted away from the masked detective, and explored one-shot short story scenarios, usually of a highly ironic "twist of fate" nature--forerunners of both the EC "SuspenStory" format and later TV shows such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone.

"Dr. Drew" may have offered a welcome creative spark for Team Eisner. While Eisner created the series concept and grandfathered the look and feel of the debut story, he left the creative work to the team of Mercer, Grandenetti and Kangeson.

Grandenetti commented on his artwork for "Dr. Drew:"

I did try to do an Eisner look on [the series] -- an impossible task -- but shortly afterwards I began to do my own thing.

For the first eight or so stories, "Dr. Drew" is consumed by the Eisner Studio "house style." in a spectacular display of innovative approaches to page layout, visual communication, ligature and graphic usage of text. If Grandenetti devised the page layouts, and the flow of information in these stories, then he learned -- and was clearly very inspired -- from Eisner's forward-thinking ethos.

That the stories are genuinely well-written, atmospheric and impressive is something of a triumph. Sheer formalism, for its own sake, can only do so much. "Dr. Drew"'s blend of substance and style is a true rarity in 1940s comics.

These stories are jarring when encountered in the context of Rangers Comics. After one gets accustomed to the Eisner-esque visual trappings (Kangeson's lettering and Grandenetti's rich backgrounds are identical to their contemporary Spirit work), the sheer quality of the series remains striking.

Yes, they look like they were filmed on the Will Eisner backlot. But "Dr. Drew" transcends its stylistic debt with highly original, vibrant visual storytelling.

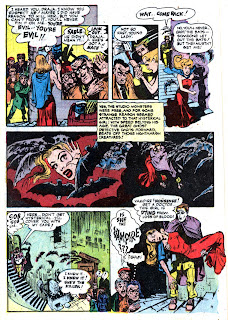

Here's one of my favorites in the series, from Ranger Comics #52. It best shows the odd mix of old-world and new-world that is "Dr. Drew," and it has a character modeled on cult film actor Bela Lugosi.

The placement of blacks, the free-wheeling approach to page layout, the notebook motif... all these were key components of the post-war Spirit. It is fascinating to see the Eisner approach slightly shifted, as it is guided by other hands.

Here's another favorite story, from issue #50. It's a variant on the Faust-Mephistopheles legend, given a suspenseful approach much like Alfred Hitchcock's 1940s films. Again, strong writing bolsters the visual pyrotechnics and prevents them from being an empty, self-indulgent grandstanding.

The visual hijinks of "Dr. Drew" toned down after its first eight installments. Page layouts became more earthbound, and the Eisner house style phased out. In their place was Grandenetti's strong, more traditional cartooning, in the au courant style of Alex Toth, Bill Draut or Pete Morisi.

Here's a sample page from the final "Drew" episode, in Rangers Comics #60:

Traces of the earlier, more flamboyant approach still remain (and, to be honest, I selected the most extreme page of this story). The style of the figures now resemble the look of the post-Eisner Spirit episodes. It seems obvious that Grandenetti assumed more of that series' art chores in 1951.

Grandenetti has continued to produce innovative, graphically arresting comix work--he contributed some strong, stylized material for the Warren horror magazines of the 1960s, and endowed DC Comics' war features with more grit and style than they deserved in the 1970s.

"The Secret Files of Dr. Drew" remains an intriguing side-project in comix history. If The Spirit was Will Eisner's Citizen Kane, "Dr. Drew" is his Journey Into Fear--a relentless excursion into visual style.

Though it stayed within the boundaries of genre tradition and audience expecation, the feature was blessed with narrative substance. While the other contents of Rangers Comics seem unreadable today, "Dr. Drew" still has something to offer 21st century readers.

_02.jpg)